Springbrook Rescue

Springbrook Rescue

Springbrook Rescue

Springbrook Rescue

| Home | The Vision | Springbrook — A Natural Wonder | The Springbrook Rescue Project | Support the Project | About ARCS |

|

Springbrook Fungi Fungi — the most colourful, diverse, and ecologically fundamental Kingdom on Earth Surveying and identifying fungi are important aspects of Springbrook Rescue. They can give clues as to whether restoration is proceeding naturally or needs our help. Fungi are essential for the health and survival of almost all ecosystems. In fact, plants would not have been able to colonise the earth half a billion years ago without a partnership with fungi. They are a biological Kingdom in their own right, separate from animals, microorganisms, and plants, but are closer to animals than any other group of living organisms. There are potentially 1.5 million or more species of fungi on earth but only 6–7 per cent are formally known or described. It is thought that the total number of fungi in Australia may be 50,000-250,000 species of which only 11,846 are described (including 3,495 lichens) and most are unique to this country. They control the fundamental carbon, water and nutrient fluxes that support life on earth, which in turn determine the diversity of species, their interactions with each other and the environment, and the myriad feedback loops amongst them that are so critical to long-term ecosystem resilience. Fungi have many functions within ecosystems — as decomposers, symbiotic partners, nutrient cyclers, food sources, habitat creators and soil conditioners. Given their great diversity, ecological significance and specialised life styles, long-term fruiting body surveys of ectomycorrhizal fungi in particular constitute an extremely valuable, efficient indicator of ecosystem health and successional trends in ecological restoration projects. Fungi are heterotrophic and thus must gain their carbon nutrition from external organic sources. At a broad trophic level, fungi are either Saprobes Mutualistic symbionts Mycorrhiza The arbuscular mycorrhizas (VAM) are members of the Glomeromycota phylum. Though not species rich (only 230 described species) they are the most ancient, abundant and widespread of all fungi. They are nearly all obligate symbionts and provide vital phosphorus and nitrogen supplies to more than 80% of land plants which, in return, provide the fungi with sugars manufactured by photosynthesis. Their spores are large and readily detectable in soil extracts with a low-powered dissecting microscope. Most ectomycorrhizal (ECM) fungi are macrofungi with readily visible fruit-bodies such as ‘mushrooms’ above ground, and truffles below. Fruit-body production is highly seasonal, irregular and patchy. Some fungi do not fruit for years; others are too cryptic to be noticed easily. They are members of either the Ascomycota (clubs, cups, flasks, jellies) and Basidiomycota (agarics, boletes, chantarelles corals, earthstars, polypores, puffballs, stinkhorns) and associate particularly with roots of the Casuarinaceae, Fabaceae (Mimosoideae, Papiloinoideae), Meliaceae, Myrtaceae, Nothofagaceae, Nyctaginaceae, Phyllanthaceae and Rhamnaceae plant families. Erecoid mycorrhizas, mostly from the Ascomycota, are indispensible partners of plants in the Ericales order. These generally occur in stressful environments on ancient, highly weathered, nutrient-poor soils. At least 13 members of the Ericaceae occur at Springbrook in forests and heaths on depauperate rhyolite-derived soils. Orchid mycorrhizas, mostly from the Basidiomycota, are likewise critically important for germination of miniscule orchid seeds that have virtually no energy reserves of their own. Endophytes Commensalist symbionts Parasitic/Pathogenic symbionts

| |||

Ecosystem engineers The Queensland Mycological Society (QMS) and the Australian Rainforest Conservation Society (ARCS) have undertaken fungi surveys since 2007, at a range of different sites at Springbrook, as one of several projects ARCS is undertaking to document the area’s rich biodiversity. We have had the generous help of many mycologists in their private capacity: Drs Diana Leemon (Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry, QLD), Richard Robinson (Department of Environment and Conservation, WA), Sapphire McMullan-Fisher (mycologist, WA) and colleagues from QMS, as well as Nigel Fechner (Queensland Herbarium). To date we have provisionally identified 203 taxa either to species or genus level in 2 phyla, 9 classes, 26 orders, 54 families, and 111 genera. The ARCS photographic fungi collection contains over 1500 images of which those below are but a small selection. Fungi are divided into two major groups. Phylum Ascomycota and Phylum Basidiomycota. Ascomycota includes Clubs and Cups; Basidiomycota includes Agarics, Chantarelles, Boletes, Polypores, Leathers, Corals, Jellies, Earthstars, Puffballs and Stinkhorns. ASCOMYCOTA |

| Clubs Trichoglossum hirsutum (Geoglossaceae) in the Lelotiales Order, with finely hairy surfaces, is one of several black “earth tongues” generally occurring amongst moss. The “hairs” are actually elongated sacs which hold spores. There are three Australian species in the genus, T. hirsutum being cosmopolitan in its distribution. |

Photo: © Aila Keto |

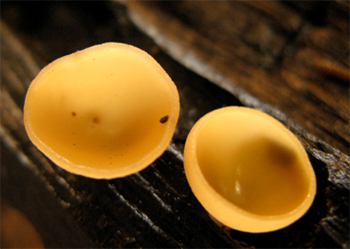

Cups |

Photo: © Aila Keto |

|

BASIDIOMYCOTA | |

Agarics Marasmius elegans |

Photo: © Aila Keto |

Cyptotrama asprata (Marasmiaceae) a saprobe on decaying woood in tropical and subtropical forests It is one of the common, but most beautiful mushrooms. |

Photo: © Aila Keto |

Agaricus bitorquis (Agaricaceae) Gills are dark chocolate to black. Found on abandoned pasture on one of the Springbrook Rescue restoration sites. |

Photo: © Aila Keto |

| Coprinellus disseminatus (Agaricaceae) |  Photo: © Aila Keto |

Gymnopilus junonius (Cotinariaceae) Webcaps are one of the easiest to identify because of the distinctive reddish veil girdles or “bracelets” on the stems. Often there are 2 to 4 of these marks. On this individual the marks have faded. |

Photo: © Aila Keto |

| Cotinarius sp. (Cotinariaceae) another webcap found on ANKIDA, a biodiverse property owned by ARCS to protect, study and restore. |  Photo: © Aila Keto |

| Phaeocollybia sp. (Cortinariaceae) a saprobe, often associated with cool temperate rainforests; deeply rooting to buried decaying wood |  Photo: © Aila Keto |

| Favolaschia pustula (Mycenaceae) an uncommon, unusual agaric where the fertile surfaces are pores rather than gills. | |

Chantarelles |

Photo: © Aila Keto |

| Boletes Strobilomyces vetulipes (Cotinariaceae) Found by Dr Keith Scott in rainforest along side Waterfall Creek on Ankida, a biodiverse property owned by ARCS for its protection, study and restoration. |

Photo: © Aila Keto |

Polypores |

Photo: © Aila Keto |

Microporus xanthopus Yellow-footed Tinypore (Polyporaceae) a saprobe on rotting wood The funnel-shaped caps are often wavy and can hold water. The undersurface is white with tiny pores. It is found in tropical Australasia, Asia and Africa but absent from America. |

Photo: © Aila Keto |

Leathers |

Photo: © Aila Keto |

Stereum sp. (Steareaceae) These are saprobic on dead wood. The underside is smooth, lacking a pore surface, and so is a crust fungus rather than a polypore. |

Photo: © Aila Keto |

| Corals Artomyces pyxidata (Auriscalpiaceae) a delicate branching coral fungus on decaying logs in high-altitude Beech forests at Springbrook. |

Photo: © Aila Keto |

| Clavaria amoena (Clavariaceae) an ectomycorrhizal fungus found amongst leaf litter in high altitude rainforest |  Photo: © Aila Keto |

| Jellies

Dacrymyces s.l. (Dacrymycetaceae) |

Photo: © Aila Keto |

Tremella globispora (Tremellaceae) The name Tremella is from the Latin tremere “to tremble” because of its jelly-like nature. All Tremella species parasitise other fungi – mainly wood-rotting fungi in both Ascomycota and Basidiomycota, especially on dead attached branches. This example was on the bark of a dead tree trunk. |

Photo: © Aila Keto |

| Earth Stars Aseroe rubra Starfish Fungus (Phallaceae) a saprobe found amongst pine bark on one the Springbrook Rescue restoration sites. |

Photo: © Aila Keto |

Puffballs |

Photo: © Aila Keto |

Cyathus stercoreus (Nidulariaceae), a saprobe on dung or dung enriched soils. Found in abandoned pasture on one of the Springbrook Rescue restoration sites. |

Photo: © Aila Keto |

|

SLIME MOULDS | |

|

Slime moulds are peculiar protists that normally take the form of amoeba but also develop fruiting bodies that release spores, and are superficially similar to the sporangia of fungi. | |

| Myxomycota Stemonitis splendens (Stemonitidaceae) a saprotrophic slime mould on decaying wood. These are one of the most distinctive slime moulds. It fruits in clusters on dead wood and has distinctive tall brown sporangia supported on slender stalks. |

|

| Stemonitis sp. (Stemonitidaceae) |  Photo: © Aila Keto |